ORIGIN STORY

(PDF)

Georgie Payne

Jenson Leonard (b. 1990) began making memes under the alias

@CoryInTheAbyss in 2015 at the age of twenty-five. Drawn to

the immediacy of the meme format, Leonard was captivated by

the ability to create and post content to various social

media platforms and message boards almost instantaneously to

reach audiences both far and wide. A

2017 Seattle Weekly article recounts how he turned to memes after receiving his MFA in

Creative Writing (with a focus on poetry) from Pratt

Institute, New York. In the article, he states: “I

felt frustrated with its [poetry’s] ivory-tower

elitism. With a poem, you might get published in a journal,

and then a few people in academia might read it. When I make

a meme, I post it, and almost right away it reaches

thousands, sometimes hundreds of thousands of people.

It’s immediate, and honestly, probably the most

pragmatic way to reach people now.”

The University of Oxford–trained biologist Richard

Dawkins, in his seminal 1976 book The Selfish Gene,

coined the term “meme” to define a unit of

cultural transmission or imitation. An expansion of Charles

Darwin’s concept of genetic evolution, Dawkins’s

theory holds that humans evolved both through biological

genes and through cultural memetics. Wide ranging in its

definition, Dawkins’s idea of a meme includes anything

from ideas to behaviors that are passed from person to

person.

By the mid to late 1990s, with the commercialization and

introduction of the World Wide Web in homes across the

world, a new concept of the meme was introduced into the

public consciousness—the internet meme. The

proliferation of the internet meme resulted in an evolution

of the mainstream definition of the term “meme”

itself, ultimately overshadowing Dawkins original concept.

Today, “meme” refers to content spreading online

from user to user, most prominently on social networking

sites, direct messaging platforms, and public web forums.

Today’s memes can take many different formats—a

still image, an animated GIF, or even a video—but they

are most recognizable as low-res images or screenshots

paired with comedic text. Often created in response to

specific events—whether stories from the global news

cycle or bespoke inside jokes—internet memes are

remixed and transposed to demonstrate a wide variety of

takes on the original source material, information, or

event.

As Leonard recounts in a 2017 interview with writer manuel

arturo abreu for AQNB, entitled“Still I Shitpost: Cory in the Abyss on a Communism of the

Visual + Anti-Blackness in the Meme-o-sphere,” he originally began making work in the standard

“Twitter format” (the modern-day version of a

caption contest, featuring an image or screenshot in a white

box with black text above or below), but his format quickly

shifted within the first year, evolving into a more ornate

and heavily parodic style of the original content (OC) he is

known for today. He states:

My work exists within the framework of meme and poor digital

image, but it distinguishes itself from the herd through its

thick pop cultural plaster. When one encounters a Cory In

The Abyss meme, my hope is that they see something that

looks like it was produced by more than one person (in a way

it is). I want my work to look and feel like a microdose of

big-budget Hollywood detritus. I want people to ask

themselves why my memes are so extra, to question their

production value, and the absurdism behind that (because the

locomotive subsumption of creativity into capitalism is

absurd). The aesthetic maximalism of my memes is my way of

finessing on white meme bros, but it’s also a means of

grabbing the audience’s attention through a visual

language capitalism has already inundated them to pay

attention to. Once I have pulled them in, finally, through

that subterfuge, giving them my message. After that

they’re free to keep scrolling.

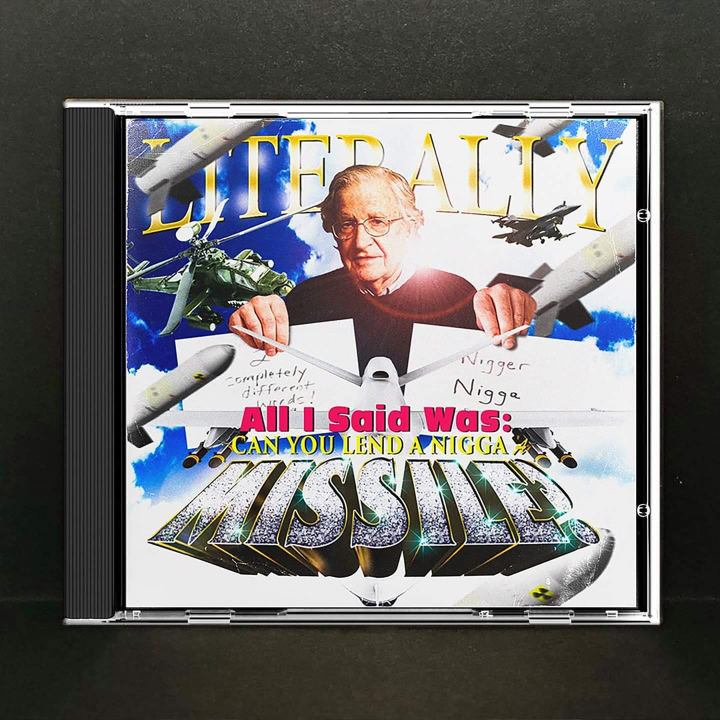

The aesthetics of Leonard’s work employs the visual

language of American capitalism, already familiar to his

audiences, to draw the viewer into far more complex

theories. His imagery illustrates the paradoxes and

complexities of the inner workings of meme culture,

specifically in relation to the co-option and

commercialization of Black culture and online vernacular

which has been brilliantly and thoroughly theorized by

scholars and writers including, but not limited to,

manuel arturo abreu,

Aria Dean,

Legacy Russell,

Lauren Michele Jackson, and

Doreen St. Félix. Furthermore, he illustrates what arturo has termed

“online imagined Black English,” which describes “the phenomenon of non-Black English

speakers with no fluency using real or imaginary linguistic

features of Black English”—exemplifying how

disembodied and essentialized versions of Blackness have

been commodified and reappropriated by white and other

non-Black bodies, both online and off.

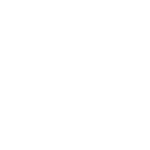

In the 2017 work Burnt Cork 2.0, Leonard employs DC

Comics superhero Cyborg to orchestrate a direct

confrontation with his audience, specifically his white and

non-Black fellow meme creators, regarding their

commodification of performative online Black affects for a

certain kind of “cool factor.” Paired with an

image of Cyborg’s half-man, half-robot body positioned

at the ready to take on anyone who dares cross him, the

work’s text states, “You wouldn’t last a

week without digital Blackface.” Leonard again

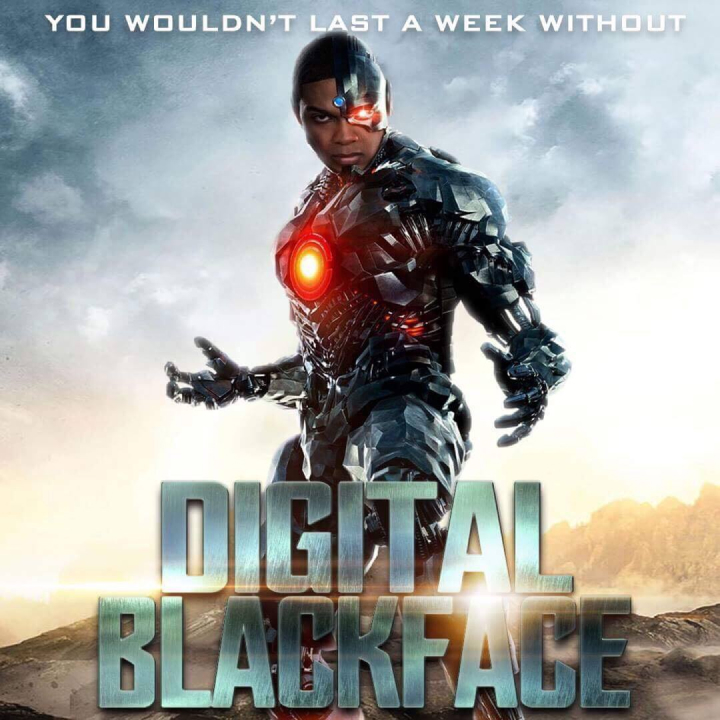

addressed this subject in 2020 with Gwan Online, an

even more literal translation of the minstrel performance of

a new era.

In many ways, Leonard’s work can be traced to several

distinct histories within contemporary visual art that have

used popular culture and mainstream media platforms to

satirize and critique social structures and patterns of

behavior, particularly in relation to race, class, and

gender. The foremost connection is the culture jamming

movement of the 1980s—a form of tactical media protest

used to disrupt or subvert mainstream media and corporate

advertising to expose their questionable modes of operation.

The movement, which itself can be seen as an adaptation of

the 1950s technique of

détournement developed by the avant-garde

artist-activist group the Situationist International, turned

the capitalist system and its media culture against itself,

subverting the original meanings of its advertising slogans

and logos toward radical ends. Artists and collectives of

this genre, including the Yes Men, Adbusters Media

Foundation, and the Billboard Liberation Front, appropriated

iconography from megacorporations ranging from

McDonald’s to Marlboro to critically engage audiences

to reflect on these industries’ corrupt production

practices and the evils of the capitalist system.

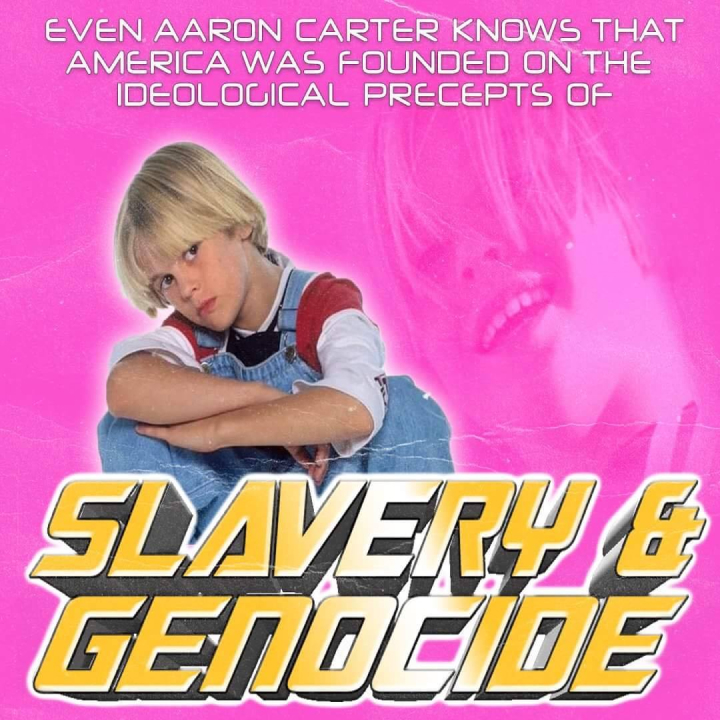

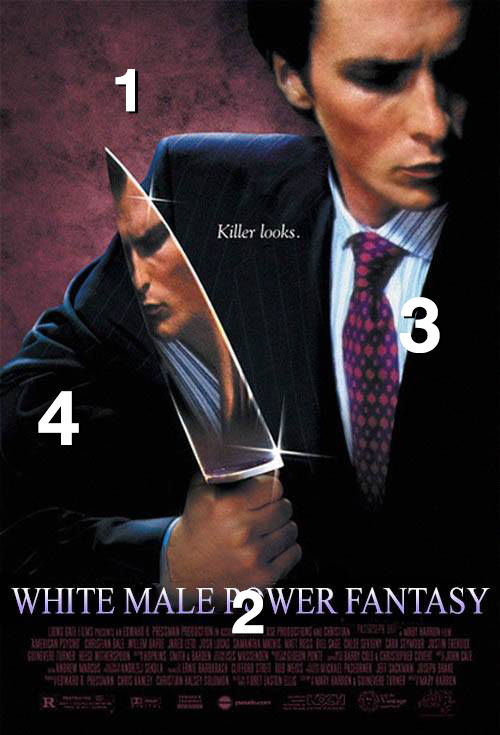

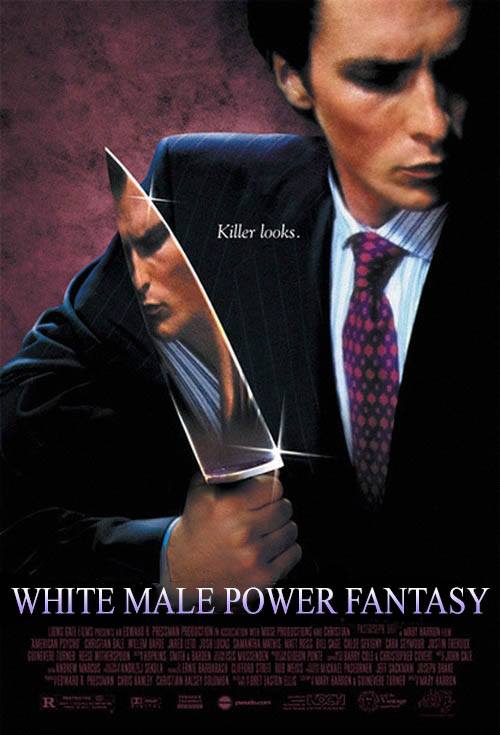

Much like the work of the culture jamming movement,

Leonard’s practice pits pop cultural icons and the

mainstream media advertising universe against itself,

subverting the original messaging to convey radical

ideology. In the digital “abyss” in which

Leonard operates, Y2K pop stars such as Beyoncé,

Aaron Carter, and *NSYNC become comrades of political

philosophers like Guy Debord, Karl Marx, and Angela Davis.

Advertisements for iconic fast-casual American restaurants

like Ruby Tuesday and Applebee’s become beacons for

the impending race war, harbingers of radical race and class

consciousness. Tyler Perry’s Madea film

franchise is reimagined through the lens of the

Combahee River Collective,

championing “Madea’s Proletariat

Uprising.” Meanwhile, the poster for slasher film

American Psycho(2000) is recast in a more honest

light as “White Male Power Fantasy.”

Furthermore, Leonard continues in this lineage with an

adaptation of one of his most iconic works, ancient white proverb, displayed on a billboard located on U.S. Route 9, in

Tivoli, N.Y., from April 19 to May 10, 2021, hacking

into public advertising to insert one of the artist’s

works both online and AFK (away from keyboard).

At the same time, Leonard’s work is also the latest

iteration in a history of net art practices, not only

because of its location and circulation as a born-digital

artwork on social media platforms and in its latest

iteration as this artist-made, browser-based exhibition, but

also because of the ways it has used web space as a place

for critique. Specifically, his work follows in the

footsteps of artists who have used satire and the medium of

the web to critique dominant white society and underscore

social contradictions of Western society. Leonard’s

practice falls into a lineage of net art from the ’00s

that exercises similar elements of contemporary meme

practices, subverting user-driven web platforms to stage

interventions into web space. We can look at Leonard’s

work as related to works such as Mendi + Keith

Obadike’s

Blackness for Sale (2001), Damali Ayo’s Rent-a-Negro(2003), and Jayson Musson’s

Art Thoughtz (2010–12). All these artists exercise comedic prowess

and digital know-how to satirize expected forms of racial

performativity in relation to the white gaze and the

essentialized version of Black identity that has been

created and maintained by and for white audiences. While

Musson’s Hennessy Youngman persona refers to this as

the “Jazz principle”—that is, white desire

for “the exotic other”—sociologist and

civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois introduces this

concept as “double consciousness,” the long-held

theory that Black Americans have developed a dual sense of

self: the ability to see themselves both as they are and as

they are perceived by a white viewer.

Furthermore, Leonard’s practice, much like Ayo and

Musson’s works, suggest a link to a history of Black

comedy that has used humor to speak critically both to and

about white audiences — drawing connections to the

work of stand-up legends such as

Dick Gregory,Godfrey Cambridge,Richard Pryor,

Wanda Sykes,

and

Dave Chappelle. As the late, great Gregory once said, “You can’t laugh social problems out of existence,”

but you can use it as a tool—which is what

these comics have done, using their comedy routines to

confront and name the unmarked nature of white normative

bodies, values, and social practices. This history exists in

what literary and Black studies scholar Christina Sharpe

calls “the wake” of the catastrophic violence of

the American Atlantic chattel slavery system and its

continued unresolved legacies. As media scholar Bambi

Haggins outlines, Black American humor, from Civil

War–era minstrelsy to stand-up comedy of the civil

rights era and beyond, has always been a marker for race

relations, both in “how much they have changed and how

much they have stayed the same over time.”Though the

medium might change, the joke stays the same— a marker

of the “progress” made.

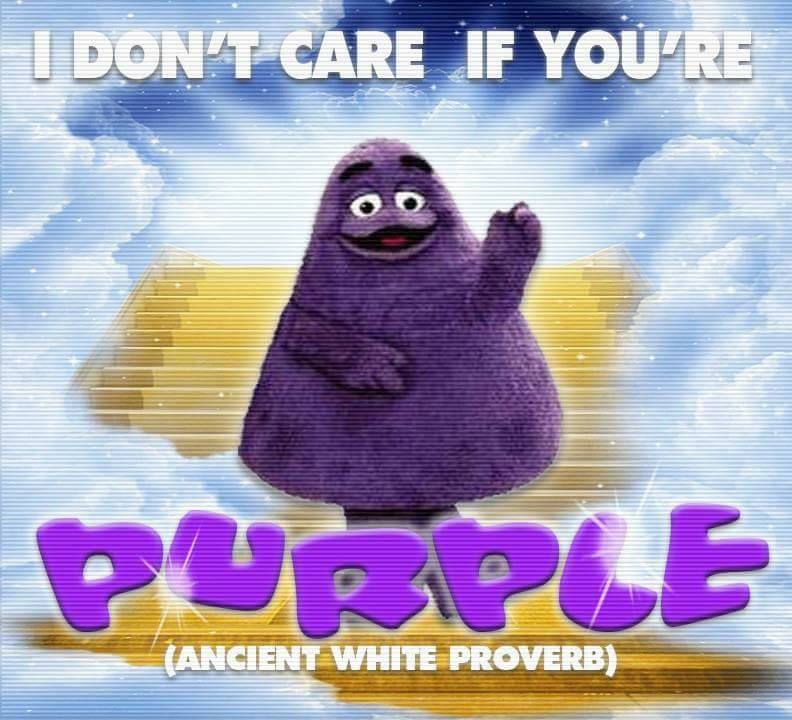

In Ancient White Proverb (2016), Leonard

repurposes Grimace, a fuzzy purple character featured in

McDonald’s advertising, to playfully take on the

evasive

“I don’t see color”

trope. The text reads “I don’t care if

you’re purple (Ancient white proverb).” Grimace,

in this instance, is not in fact being used as a tool to

reflexively critique the McDonald’s corporation, but

instead to call out the “I don’t care if

you’re purple, green, or polka-dotted” platitude

that often circulates in liberal-leaning white circles.

Though the colors invoked might change, the result of

uttering the phrase stays the same: it’s a deflective

attempt at the ever elusive racial neutrality that downplays

the realities of how race operates in society, and a

conflation of the very real histories and realities of BIPOC

lives with that of nonexistent purple, green, and

polka-dotted people. Furthermore, the phrase implicates a

flawed understanding of racism as simply the work of

singular individuals and their actions—the “bad

apple” mentality—rather than as a systemic

function of society.

In an August 2020 online panel discussion entitled “Race Jam: A Panel on Memes and Online, Imagined

Blackness” (hosted as part of Leonard’s residency at the

Buffalo, N.Y.–based arts organization

Squeaky Wheel), the artist addressed the many ways in which

“Blackness, Black culture, Black affect, Black

vernacular” has been “extracted, surveilled, and

commodified down to the nearest Nae Nae.” Speaking

with fellow meme creator panelists

Ashley Khirea Wahba,

Nicolás Vargas, and

Pastiche Lumumba, Leonard shared how his follower count rose following the

state-sanctioned murder of George Floyd at the hands of

Minneapolis police earlier that summer. Acknowledging the

harrowing set of circumstances that gained him over 2,000

followers in a week, Leonard stated:

I’m not encouraged by that. I’m deeply disturbed

by the fact that the increased visibility of my meme page

and my content is intimately tied to Black death. And it

took a succession of Black people dying for white meme pages

to be like “Hmm, well, maybe this might be a good

idea,” and that really fucks with me and makes me not

want to participate in this thing. Because now it’s

tainted. My page growth is now associated with that

fuckshit.

Here, Leonard is articulating what critic, artist, and

curator Aria Dean reminds us of in her 2016 essay “Poor Meme, Rich Meme”:

“These videos proliferate alongside memes, brushing up

against each other on the same platforms. Further, black

death and black joy are pinned to each other by the white

gaze.” While his viewership went up following

Floyd’s death, Leonard’s drive to produce

content went down, specifically in response to not wanting

to appease his new white viewership and pushing back against

the infinite scroll of the internet and the tireless

production of online content.

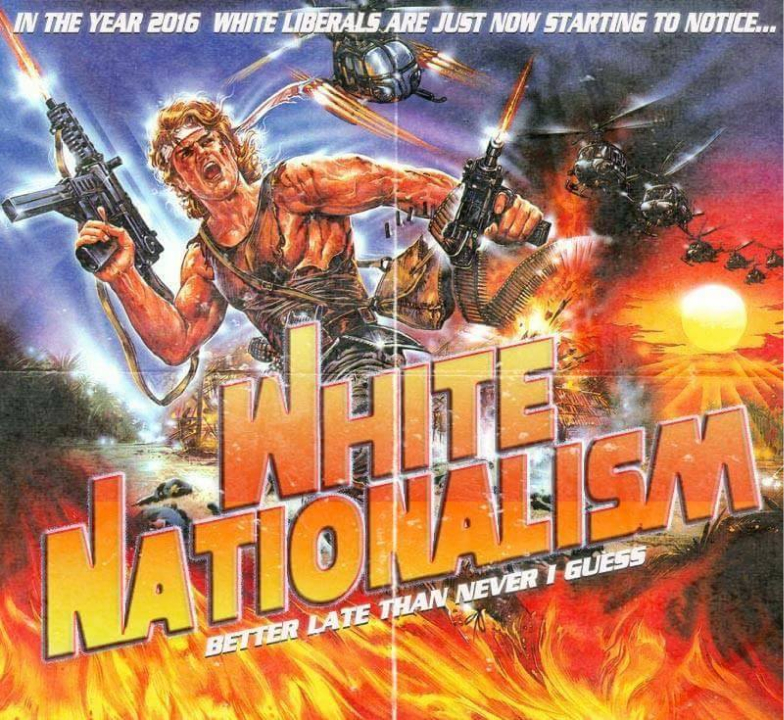

In a work entitled BLTN (read: Better Late Than

Never), a muscular white Rambo-esque man lets out a roar as

he runs from a swarm of helicopters quickly approaching

behind him. He holds a machine gun in each outstretched arm

while a blaze of fire engulfs the bottom of the frame. The

text on top reads: “In the year 2016 white liberals

are just now starting to notice . . . White Nationalism.

Better late than never I guess.” The artists describes

the work as being “spurred by [his] amusement in the

uptick of newfound political awareness amongst white

liberals about the nationalist elements that have always

permeated American politics, but became more legible when

the president was explicitly white supremacist, as opposed

to prior, more tacitly white supremacist

administrations.” Following in the same vein,

Yacubian Cave Trickery (2019) depicts Captain

Caveman from the 1970s Hanna-Barbera cartoon shouting,

“Me go to anti-racism workshop, me fix racism!”

While made the year before, the work remained relevant in

the summer of 2020 as performative allyship spreading online

reached an apex. Leonard, through addressing the

“marketized logic of the anti-racism industrial

complex,” notes how these topics remain relevant

within his work yet fade in and out of algorithmic fashion

within the larger culture. While anti-racist resources,

training workshops, and readings lists were the dominant

topic of conversation on influential social media platforms

this past summer, they slowly began to fade out of our

timelines, almost entirely gone by the time the first leaf

fell in autumn.

While it’s hopeful that for many white people

this moment was a powerful “wake up” call about

the existence of systemic oppression and racism, these works

point to the fact that “the work” is not over

after one workshop, one book, or one Instagram post. In his

2009 book Black Is the New White, Paul Mooney,

legendary comedian and frequent collaborator of Richard

Pryor, writes: “For white people, watching the Rodney

King video is like a world premiere movie. ‘Oh, I

didn’t know the nice policemen did that.’ For

Black people, it’s a rerun. It’s been in

syndication for a long time. We’ve seen it all

before.” This apathetic white attitude perpetuates

across time, and was more recently satirized by filmmaker

Chester Vincent Toye’s comedic short

I’m SO Sorry

(2021) and personified by

Saturday Night Live’s Beck Bennett in a

satirical commercial advertisement for

5-Hour Empathy

during an October 2020 episode. Given the opportunity to

drink “five full hours of complete intimate

understanding of systemic oppression and ever-present

racism,” the white male main character (and later his

white wife) find every possible excuse to delay accessing

the knowledge they claimed to desperately want to know,

exposing performative forms of activism for what they

are—all talk and no action.

In recent months, rather than working overtime within the

tireless production cycle to create work that appeals to his

newfound audience, Leonard has directed his practice to

become even more intentional. The

Yacht Metaphor exhibition is designed to enable

viewers to engage longer and deeper, and to consider the

works’ continued relevance and messaging, particularly

within extended histories of artistic expression and

critique. Offering an experience that is distinctly separate

from algorithmic mediation, the exhibition frees the memes

from the grasp of the dominant social media platforms on

which they typically circulate, inviting viewers to stop the

scroll and explore the significant layers of history,

reference, and knowledge hidden within the abyss.

Endnotes

-

manuel arturo abreu, “Still I Shitpost: Cory in the

Abyss on a Communism of the Visual + Anti-Blackness in the

Meme-o-sphere,” AQNB, December 12, 2017,

https://www.aqnb.com/2017/12/12/still-i-shitpost-cory-in-the-abyss-on-a-communism-of-the-visual-antiblackness-in-the-meme-o-sphere-with-manuel-arturo-abreu.

-

Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene, 40th Anniversary ed.

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

-

Jenson Leonard, “An Interview with Jenson Leonard on

the Intersection of Poetry and Memes,”interview by

Eben Benson, Juxtapoz, June 30, 2017,

https://www.juxtapoz.com/news/collage/an-interview-with-jenson-leonard-of-coryintheabyss.

- abreu, “Still I Shitpost.”

-

Leonard refers here to artist and theorist Hito

Steyerl’‘s idea of the “poor

image.”

- abreu, “Still I Shitpost.”

-

manuel arturo abreu, “Online Imagined Black

English,” Arachne, n.d.,

https://arachne.cc/issues/01/online-imagined_manuel-arturo-abreu.html.

-

Marilyn DeLaure and Moritz Fink, eds., “Culture

Jamming: Activism and the Art of Cultural

Resistance,”Mark Dery, “Culture Jamming:

Hacking, Slashing, and Sniping in the Empire of

Sign,” in Culture Jamming: Activism and the Art of

Cultural Resistance, ed. Marilyn DeLaure and Moritz Fink

(New York: New York University Press, 2017), 58.

-

“(1977) The Combahee River Collective

Statement,” Black Past, November 16, 2012,

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/combahee-river-collective-statement-1977.

-

By using AFK, I reference Legacy Russell referencing

social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson, who prefers this

term in lieu of the more well-known shorthand

“IRL” (iIn rReal lLife), which, as Russell and

Jurgenson, argue “ is a misunderstanding, an

antiquated falsehood, one that implies that two selves

(i.e. online versus offline) operate in isolation from one

another, inferring that online activity lacks authenticity

and is divorced from a user’s ‘real’

identity, offline.” Legacy Russell, “On

#GLITCHFEMINISM and the Glitch Feminism Manifesto,.”

Res., 2016/17,

http://beingres.org/2017/10/17/legacy-russell/22 Oct. 2017. Web. 19 Mar. 2021.

-

See “INTERNET EXPLORERS” by Ceci Moss,

“Internet Explorers,” in Mass Effect: Art and

the Internet in the Twenty-First Century, ed. Lauren

Cornell and Ed Halter (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), Mass

Effect (p147)— which draws out this history,

specifically looking at artists (between 2005 and -2010)

who have chosen to forgo the traditional exhibition space,

with its excessive limitations, and instead utilize use

the digital space to exhibit their work, specifically

following the rise of major social media platforms

(Friendster, Myspace, Facebook, YouTtube, Twitter, and

Tumblr).

-

Alexander Iadarola, “What Up Internet,”

Rhizome: Net Art Anthology, January 12, 2018,

https://rhizome.org/editorial/2018/jan/12/what-up-internet/.

-

W. E. B. Du Bois, “Strivings of the Negro

People,” Atlantic, August 1897,

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1897/08/strivings-of-the-negro-people/305446/.

-

Musson’s Hennesy Youngman character is a reference

toHenny Youngman, king of the one-liners, and has reference

Def Comedy Jam as a source of inspiration ; Ayo's

work is an adaptation of Godfrey Cambridge's1965 stand-up

bit,

The Rent-A-Negro Plan, also similar to a bit Dick Greggory did around the same

time.

-

Western Washington University, “KVOS Special: Dick

Gregory,” YouTube, uploaded July 9, 2010,

https://youtu.be/75ajExLNU9k.

-

Bambi Haggins, Laughing Mad: The Black Comic Persona in

Post-Soul America (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University

Press, 2007), 21.

-

Black, Indigenous, and people of color. For more

information on this term, see Sandra E. Garcia,

“Where Did BIPOC Come From?,” New York Times,

June 17, 2020,

https://www.nytimes.com/article/what-is-bipoc.html

-

Squeaky Wheel, “Race Jam: A Panel on Memes and

Online, Imagined Blackness,” with Jenson Leonard,

Ashley Khirea Wahba, Nicolás Vargas, and Pastiche

Lumumba, YouTube, uploaded August 20, 2020,

https://youtu.be/dOtgYW5i1LQ.

-

Jenson, in “Race Jam: A Panel on Memes and Online,

Imagined Blackness.”

-

Jenson, in “Race Jam: A Panel on Memes and Online,

Imagined Blackness.”

-

Paul Mooney, Black Is the New White: A Memoir (New York:

Gallery Books, 2010), 341.